The Playbook: Arbitration Clauses in Employment Agreements

July 15, 2016

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of blogposts without express and written permission is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given, and with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

The author of this post can be reached by phone at 206-693-2718 or by email.

Legal Lessons Learned from Steve Sarkisian & USC

Part Four: USC’s Home Field Advantage Makes a Difference in the Fourth

by Stacia Hofmann

Last month, I wrote about coach Steve Sarkisian’s alcohol dependence disability claims against the University of Southern California in a fictionalized world where Washington, rather than California, law governed the dispute. Now, in my fourth installment of the blog series, I continue to use Sarkisian’s case against USC to discuss various aspects of Washington employment law. In this blogpost, I will cover arbitration clauses in employment agreements – Sarkisian’s contract had one.

What is an arbitration, and why do parties agree to use it?

Before we delve into Washington law, let’s first go over what is meant by arbitration. An arbitration is a way to resolve a legal dispute. It is like a trial, in that the parties argue a case through testimony and the written submission of evidence. But it is a very different venue: instead of a judge or jury, an arbitrator (or panel of arbitrators) decides the case. The arbitrators may be attorneys, former judges, or industry experts. Arbitration may be binding – meaning a jury trial is waived, and the arbitrator’s award is final and in most circumstances not appealable – or nonbinding.

So why do parties agree to arbitration? Well, for one thing, materials submitted in arbitration are not part of the public record, and an arbitration hearing is not open to the public. Parties who wish to keep a dispute private (like USC, who would not welcome the media attention over employment disputes) may choose arbitration.1

Additionally, arbitration is usually more efficient and definitely less formal than a trial. The “case life” for an arbitration may be a few months, as opposed to a year or more for a court case, and the arbitration hearing itself typically takes quite a bit less time than a trial. Less time spent on a case generally equals less attorneys’ fees. But make no mistake: arbitration is expensive. In some types of arbitration, one or more parties have to pay for the arbitrator’s time. The parties never have to pay for a judge’s or jury’s time,2 so when arbitrator fees are added to attorneys’ fees, arbitration can be quite costly.3

Finally, some parties believe that arbitration is more predictable than a jury, which, in turn, allows them to better manage the risks and benefits of litigation. Still, other parties disfavor arbitration because they believe that arbitrators are more biased than juries.

Washington law governing arbitration clauses in employment agreements

Arbitration can be agreed to either before or after a dispute arises. This blogpost is concerned with arbitration agreed to in an employment contract (an “arbitration clause”) in anticipation of a potential dispute or disagreement between a Washington employee and employer (called “predispute arbitration”).

Courts across the U.S. and Washington favor arbitration, as it eases court congestion and furthers the rights of parties to enter into private contracts. An arbitration clause in an employment agreement is presumed to be enforceable, although there are contractual defenses that, if strong enough, allow an employee to choose a court venue instead. For purposes of this post, we are concerned with two such defenses:

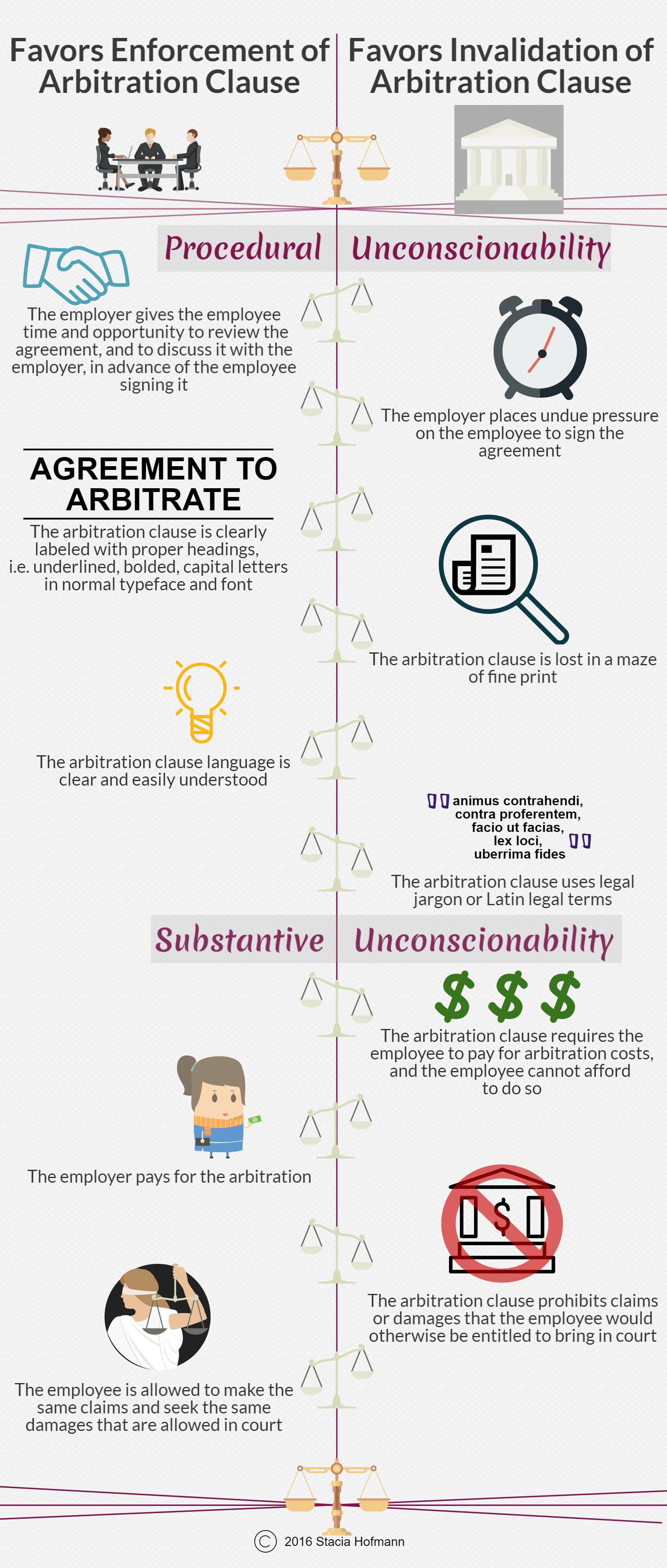

1. Procedural Unconscionability: Procedural unconscionability is legal lingo for the lack of a meaningful choice in agreeing to the arbitration clause, as shown by the manner in which the contract was entered into, whether each party had a reasonable opportunity to understand the terms of the contract, and whether the important terms were hidden in a maze of fine print.

2. Substantive Unconscionability: Substantive unconscionability is legal lingo that means that the arbitration clause is unfairly one-sided, shocking to the conscience, monstrously harsh, or exceedingly calloused.

Judges, not juries, are the ones who decide whether an arbitration clause is procedurally or substantively unconscionable, and thus whether the parties have to arbitrate the dispute instead of staying in court.

How are these legal gobbledygook defenses applied? If a prospective employee is given a standard form prepared by the employer, and is told that the only two options are to sign the agreement or forego employment, is that procedurally unconscionable? Probably not, so long as the arbitration clause is clear and unhidden, and the employer gives the prospective employee ample time and opportunity to review the contract, consult with an attorney, and discuss it with the employer.

Is an arbitration clause substantively unconscionable if the employee has to pay the arbitrator fees, since the employee would not have to pay a judge or jury for their time? Possibly, if arbitration is prohibitively expensive in that the arbitrator fees would have the effect of preventing the employee from bringing a claim. What if the arbitration clause limits an employee’s entitlement to damages under Washington or federal statutes? Probably, because such a contract would unfairly limit the employee’s right to recover what the legislature previously determined was proper.

There are many different factors that a judge may analyze in deciding whether an arbitration clause is unconscionable:

Why is the arbitration clause a home field advantage for USC?

Turning back to the dispute between Sarkisian and USC, Sarkisian initially filed a lawsuit in court. USC argued that the case should be arbitrated pursuant to an arbitration agreement. Sarkisian argued that he did not remember signing the two-page document. After USC filed a motion to move the case into arbitration, Sarkisian agreed to arbitrate his claim.4

Why is this a benefit to USC? Because USC chose the venue. The University has more of an interest in keeping the dispute private than Sarkisian does, regardless of the merits of Sarkisian’s claims. News stories about Sarkisian’s alcohol use had already badly tarnished his image by the time he filed suit. On the other hand, USC is working on rebuilding its football program after NCAA sanctions for violations occurring during the Pete Carroll era, the subsequent, mostly mediocre reign of Lane Kiffin, and finally the Sarkisian firestorm. USC had been hit with a triple whammy in its football program (not to mention scandals within its basketball and tennis programs), and has more to lose from further bad publicity. The leverage that Sarkisian had in the court of public opinion is gone.

I will be writing one more blogpost in this series to summarize how Washington businesses can learn from the legal issues in the Sarkisian v USC dispute.

This blog is for informational purposes only and is not guaranteed to be correct, complete, or current. The statements on this blog are not intended to be legal advice, should not be relied upon as legal advice, and do not create an attorney-client relationship. If you have a legal question, have filed or are considering filing a lawsuit, have been sued, or have been charged with a crime, you should consult an attorney. Furthermore, statements within original blogpost articles constitute Stacia Hofmann’s opinion, and should not be construed as the opinion of any other person. Judges and other attorneys may disagree with her opinion, and laws change frequently. Neither Stacia Hofmann nor Cornerpoint Law is responsible for the content of any comments posted by visitors. Responsibility for the content of comments belongs to the commenter alone.

- Still, in some instances, the arbitration award may be filed publicly with the court. ↩

- Courts do require filing fees, including for a jury, but filing fees in court will typically total less than $1,000 from start to finish. ↩

- For a Seattle arbitrator’s perspective on arbitration clauses in employment agreements, click here. ↩

- Click here to read ESPN’s story about the arbitration clause dispute. ↩