Retailer Liability: Self-Service? No Notice? No Problem.

January 19, 2017

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of blogposts without express and written permission is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given, and with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

The author of this post can be reached by phone at 206-693-2718 or by email.

When Customers Access Goods on Their Own, the Risk of Liability Increases

by Stacia Hofmann

A recent Eastern Washington case filed against Wal-Mart shows that a retailer can be liable for something as unusual as a wild animal bite. The case, involving a rattlesnake and discussed in more detail below, provides another opportunity to focus on the importance of managing the risks of “premises liability” claims. In broad terms, premises liability is a land possessor’s legal and financial responsibility for an injury on the premises. It is a type of negligence, which means it has roots in foreseeability, reasonableness, and the duty to exercise due care for the safety of others. Premises liability has many nuances and is incredibly varied. I previously wrote about how dog bites and slip and falls can lead to premises liability claims.

In this blogpost, I will be discussing a special type of premises liability in Washington, referred to by lawyers and judges as the “Pimentel Exception,” which sounds more like an indie film title or an exciting dish at a trendy restaurant than a rule of law.1 Businesses that allow customers to self-serve — access and handle goods and products without an employee’s involvement — can benefit from understanding the Pimentel Exception, and from using risk management to prevent and minimize premises liability exposure and losses.

Before we delve into the Pimentel Exception, we first need to cover the concept of notice. One way for an injured party (a “claimant” or “plaintiff”) to prove a premises liability claim is to show that the business’s employees or other representatives had actual notice — actually knew — of a dangerous condition on the premises, and did not exercise due care to warn of or fix the condition.

Actual notice sets a pretty high bar, so the law also allows an injured party to prove a premises liability claim by showing that, even absent actual knowledge, the condition existed for long enough and under such circumstances that a business’s employees could and should have reasonably discovered the condition — called constructive notice.

The lack of a business’s actual or constructive notice of a dangerous condition can potentially result in the dismissal of a premises liability claim in favor of the business. But if the plaintiff can show the Pimentel Exception applies, then, under legal order from the Washington Supreme Court, the plaintiff is allowed to proceed with his or her claim without having to prove actual or constructive notice.

Washington courts have made it clear that the Pimentel Exception does not apply every time someone is injured in a retail store or restaurant. Rather, all of the following conditions must be met for the Pimentel Exception to apply:

- The unsafe condition and the injury are in a location in the business where customers self-serve, having direct access to products, goods, food/drink, or other items for sale;

- The unsafe condition is continuous or foreseeably inherent in the nature of the business or mode of operation; and

- There is a relationship between the self-service aspect of the business and the dangerous condition.

Last month, Washington’s Court of Appeals decided the case of Craig v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.2 The plaintiff was examining the price tag on a bag of mulch resting on a wooden pallet in an outdoor garden center when a rattlesnake bit his hand. The Wal-Mart employees working that day did not see the snake prior to the bite, and there was no evidence that any employee had ever seen a rattlesnake on the premises. Craig argued that he did not have to show Wal-Mart’s actual or constructive notice of the dangerous condition (the rattlesnake) because the Pimentel Exception applied. The Washington Court of Appeals agreed, concluding:

Last month, Washington’s Court of Appeals decided the case of Craig v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.2 The plaintiff was examining the price tag on a bag of mulch resting on a wooden pallet in an outdoor garden center when a rattlesnake bit his hand. The Wal-Mart employees working that day did not see the snake prior to the bite, and there was no evidence that any employee had ever seen a rattlesnake on the premises. Craig argued that he did not have to show Wal-Mart’s actual or constructive notice of the dangerous condition (the rattlesnake) because the Pimentel Exception applied. The Washington Court of Appeals agreed, concluding:

- Customers were permitted to handle and access goods in the garden center, and specifically where the bite occurred, so the injury and dangerous condition were in a self-serve location.

- Rattlesnakes are prevalent in Clarkston (the location of the Wal-Mart) and they wander. The risk of one taking shelter in Wal-Mart’s outdoor garden center, which was next to undeveloped land and lacked a barrier, was foreseeably inherent in the mode of Wal-Mart’s outdoor garden operation.

- There was a relationship between the self-service aspect and the dangerous condition because rattlesnakes could take up residence in the dirt, plants, and the other items for sale that were directly handled by customers in the outdoor garden center.

One of the three judges disagreed, concluding that there was no relationship between the self-service mode of Wal-Mart’s operation and the rattlesnake because there was no evidence that risks of rattlesnake encounters were greater in the garden center than elsewhere.

The case is a reminder that even rare or atypical events can lead to liability. Because the Pimentel Exception still requires that the danger be reasonably foreseeable, self-serve businesses should utilize risk management techniques and tools to identify, analyze, and treat those foreseeable conditions before they cause injuries to customers. This includes not only implementing policies and procedures for premises inspections and employee training, but also specifically guarding against potentially dangerous conditions arising out of customer interaction with products and product storage/display.

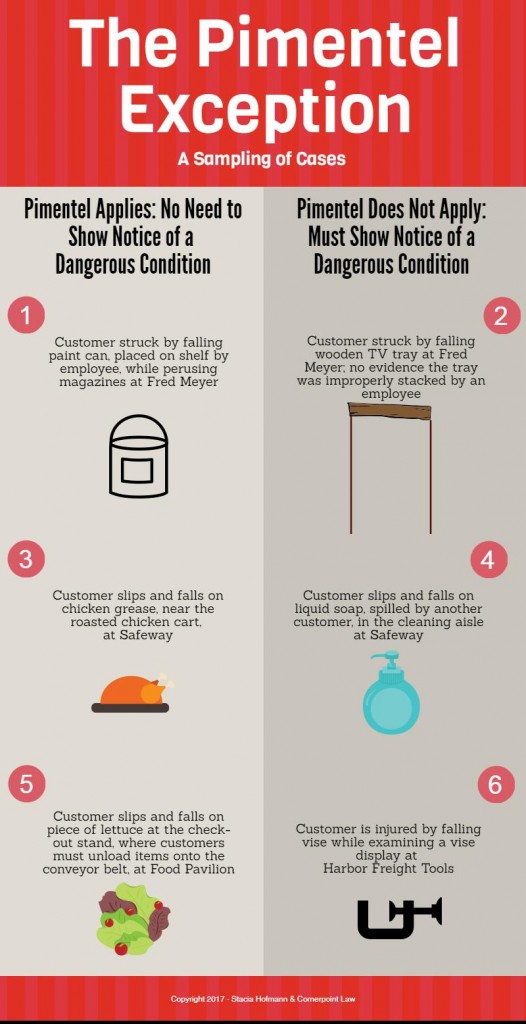

For additional context, what follows is a chart3 of several real Pimentel Exception cases decided by Washington appellate courts. The chart demonstrates that seemingly similar cases are decided differently; the distinctions are often subtle and in the details. It can be difficult to predict whether a judge will apply the Pimentel Exception in the plaintiff’s favor, underscoring why businesses should give thoughtful consideration to litigation prevention rather than waiting to battle it out in court.

This blog is for informational purposes only and is not guaranteed to be correct, complete, or current. The statements on this blog are not intended to be legal advice, should not be relied upon as legal advice, and do not create an attorney-client relationship. If you have a legal question, have filed or are considering filing a lawsuit, have been sued, or have been charged with a crime, you should consult an attorney. Furthermore, statements within original blogpost articles constitute Stacia Hofmann’s opinion, and should not be construed as the opinion of any other person. Judges and other attorneys may disagree with her opinion, and laws change frequently. Neither Stacia Hofmann nor Cornerpoint Law is responsible for the content of any comments posted by visitors. Responsibility for the content of comments belongs to the commenter alone.