If the Other Side Breaches the Contract, Can You Too?

August 27, 2021

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of blogposts without express and written permission is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given, and with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

The author of this post can be reached by phone at 206-693-2718 or by email.

Two Wrongs Don’t Always Make a Right: A Cornerpoint Case Pop

By Stacia Hofmann

Cornerpoint Case Pops are dedicated to summarizing relevant, new cases — and their business and risk management lessons — in bite-size posts.

Business owners are frequently juggling multiple relationships, dealing with deadlines and budgets, and balancing many other moving parts. So when they believe that someone else is in breach of contract, they may be tempted to breach the contract in response. But when is a party legally excused from performing its promises because the other party breached the agreement?1

The Case: Zenith Global Solutions, Inc. v. Linden Village Assisted Living Facility, LLC, Washington Court of Appeals, Division I, No. 81490-7-I (Unpublished, July 6, 2021)

Case Background

The parties entered into a real estate development contract. Zenith agreed to perform certain services for Linden in exchange for payment. Zenith filed a lawsuit, alleging failure to pay. Linden argued that it did not have to pay because Zenith had failed to perform all of the agreed-upon services.

The case went to a trial before a judge. The judge agreed that Zenith had indeed failed to perform all of the promised services, but that Zenith’s failures had not caused Linden damages. Therefore, Linden (and not Zenith) was liable for breach of contract and money damages.

One Party’s Breach of Contract Must Be Material to Excuse the Other Party’s Performance

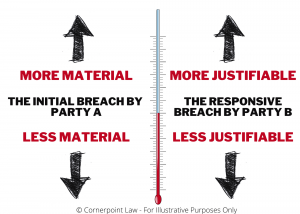

In Washington, a party may be excused from performing its promises if the other party materially breached the contract first. What does “materially” mean? Well, because every contract is different, there is no hard and fast rule. Instead, for our purposes, “materially” means that one party’s breach is so significant that it justifies the other party from having to continue with the contract promises.

In Washington, a party may be excused from performing its promises if the other party materially breached the contract first. What does “materially” mean? Well, because every contract is different, there is no hard and fast rule. Instead, for our purposes, “materially” means that one party’s breach is so significant that it justifies the other party from having to continue with the contract promises.

In this case, the trial judge found that there were no monetary consequences caused by Zenith’s failure to perform the services. So we can assume that while the judge agreed with Linden that Zenith’s services were not as promised, the judge disagreed with Linden that Zenith’s services were so out of line that Linden could just refuse payment. Linden still owed Zenith the money it had promised to pay in the contract, and, by failing to make that payment, Linden was liable for breach of contract.

Key Takeaway

A breach of a contract by one party may justify a breach by the other party. But the law allows for some flexibility in promises, actions, and behavior, so only material breaches qualify. An immaterial breach is simply inconsequential in the grand scheme of things.

There are several ways for businesses to manage the risk that a material breach will be incorrectly categorized as an immaterial breach. First, at the time the contract is written, the parties can explicitly or implicitly define what failed promises amount to material breaches. This can be useful when there are intricacies about the transaction that make otherwise minor transgressions unacceptable. Second, including an appropriate written termination clause based on a party’s individualized risk tolerance can at least act as a tourniquet to “stop the bleeding.” Finally, business contract attorneys can help assess whether a failed promise falls on the immaterial or material side of the spectrum and provide advice before a party breaches a contract in response to a suspected breach by the other party. Email or call me to see if Cornerpoint can help with your questions about contracts, promises, and breach of contract.

This blog is for informational purposes only and is not guaranteed to be correct, complete, or current. The statements on this blog are not intended to be legal advice, should not be relied upon as legal advice, and do not create an attorney-client relationship. If you have a legal question, have filed or are considering filing a lawsuit, have been sued, or have been charged with a crime, you should consult an attorney. Furthermore, statements within original blogpost articles constitute Stacia Hofmann’s opinion, and should not be construed as the opinion of any other person. Judges and other attorneys may disagree with her opinion, and laws change frequently. Neither Stacia Hofmann nor Cornerpoint Law is responsible for the content of any comments posted by visitors. Responsibility for the content of comments belongs to the commenter alone.

- I previously posted about a somewhat similar situation called anticipatory repudiation: when a party is excused from performing its contractual promises because the other party unequivocally showed that it did not intend to honor its promises. ↩

Contractual breaches aren’t a free pass to retaliate. This clear-eyed article explains why two wrongs don’t make a legal right.