Jury Verdicts: Far from a Sure Bet

March 16, 2016

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of blogposts without express and written permission is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given, and with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

The author of this post can be reached by phone at 206-693-2718 or by email.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

“I do not believe in the court system, at least I do not think it is especially good at finding the truth. No lawyer does. We have all seen too many mistakes, too many bad results. A jury verdict is just a guess—a well-intentioned guess, generally, but you simply cannot tell fact from fiction by taking a vote.” — Prosecutor Andy Barber, the fictional narrator in lawyer William Landay’s thought-provoking legal thriller, Defending Jacob1Excerpt from Defending Jacob: A Novel by William Landay, © 2012 by William Landay. Used by permission of Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Any third-party use of this material, outside of this publication, is prohibited. Interested parties must apply directly to Penguin Random House LLC for permission.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Why Manage Risk to Prevent Litigation? To Avoid Facing an Unpredictable Jury

by Stacia Hofmann

I believe in the goals and intentions of a jury trial, and it has been my experience that jurors take their jobs seriously, that they strive to be impartial, and that they seek the truth. But I still hear Andy Barber loud and clear. Jurors come into a case cold to and unfamiliar with the facts, using their own beliefs, biases, and opinions to process and interpret the evidence. Add juror preconceptions to the law’s evidence rules, which exist to keep the jury from hearing untrustworthy information but may also keep out important facts; to the time and resource commitment expected of jurors; to the demands on lawyers and judges; and to the budget constraints affecting the justice system. It is a formula with so many variables that the process may result in a verdict that seems less like a finding of truth, and more like an unfair rewriting of history.

I believe in the goals and intentions of a jury trial, and it has been my experience that jurors take their jobs seriously, that they strive to be impartial, and that they seek the truth. But I still hear Andy Barber loud and clear. Jurors come into a case cold to and unfamiliar with the facts, using their own beliefs, biases, and opinions to process and interpret the evidence. Add juror preconceptions to the law’s evidence rules, which exist to keep the jury from hearing untrustworthy information but may also keep out important facts; to the time and resource commitment expected of jurors; to the demands on lawyers and judges; and to the budget constraints affecting the justice system. It is a formula with so many variables that the process may result in a verdict that seems less like a finding of truth, and more like an unfair rewriting of history.

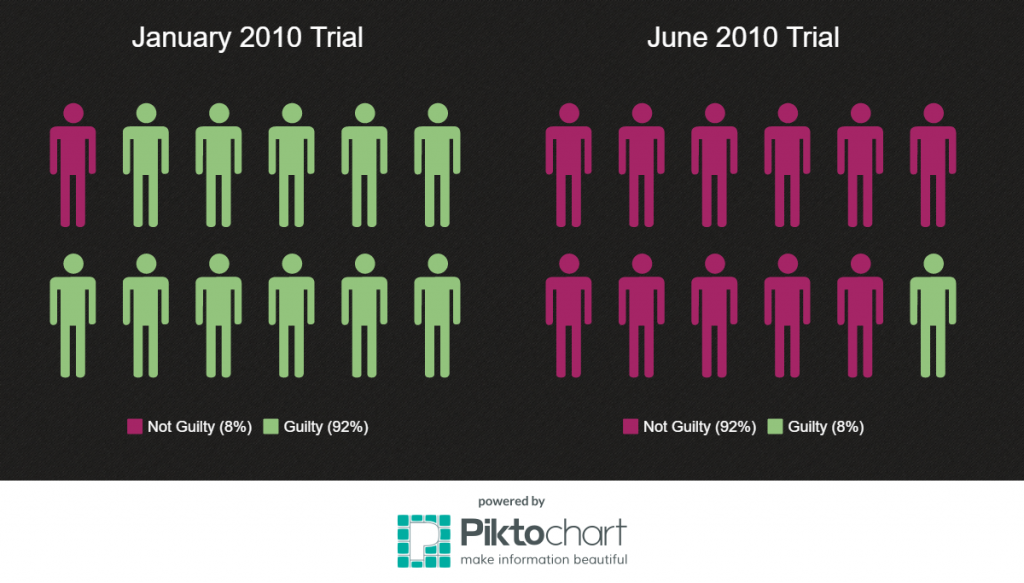

Consider this local example of juror unpredictability. In 2009, a King County deputy was accused of misdemeanor assault of a teenage girl in her jail cell. The incident was caught on video, which was presumably used as evidence.2The video was released to the public and can be viewed here, and you can read more about former Deputy Paul Schene’s trials here. Both links courtesy of The Seattle Times. In January 2010, the case went to trial. The jury could not reach a unanimous decision, which is required in criminal trials, deadlocking 11-1 to convict him. Five months later, in June 2010, the case went to trial a second time. The jury again could not reach a unanimous decision – but this time voted 11-1 to acquit! Sure, the attorneys may have changed their strategies, resulting in different degrees of effectiveness. But the facts of the incident could not have changed; rather, the two juries just reached different truths from those facts.

When all was said and done, out of a sampling of 24 people, exactly 50% felt a crime had been committed beyond a reasonable doubt, the other 50% did not. Flipping a coin offers the same odds.

So many lawsuits are avoidable, and the effects of many others can be significantly minimized, by using legal controls and risk management techniques. The best way to reduce the uncertainty of a jury verdict is to never be in a position where a jury verdict is needed. Consider trying your luck elsewhere.

This blog is for informational purposes only and is not guaranteed to be correct, complete, or current. The statements on this blog are not intended to be legal advice, and should not be relied upon as legal advice. If you have a legal question, have filed or are considering filing a lawsuit, have been sued, or have been charged with a crime, you should consult an attorney. Furthermore, the statements within the original blog post articles constitute Stacia Hofmann’s opinion, and should not be construed as the opinion of any other person. Neither Stacia Hofmann nor Cornerpoint Law is responsible for the content of any comments posted by visitors. Responsibility for the content of comments belongs to the commenter alone.

References

| ↑1 | Excerpt from Defending Jacob: A Novel by William Landay, © 2012 by William Landay. Used by permission of Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Any third-party use of this material, outside of this publication, is prohibited. Interested parties must apply directly to Penguin Random House LLC for permission. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The video was released to the public and can be viewed here, and you can read more about former Deputy Paul Schene’s trials here. Both links courtesy of The Seattle Times. |